Designing for Democracy: Imagining the Spaces That Make It Possible

In the second installment of Designing for Democracy, participants were invited to think spatially and imaginatively:

If democracy were a place, what would it look like?

What kinds of environments help democracy not only function — but thrive?

This workshop built on the first event’s reflections about how the built environment supports public life. Here, we shifted from discussion to design — translating abstract ideas about democracy into tangible spatial elements, design considerations, and civic experiences.

Participants engaging in small-group discussions during the second Designing for Democracy event. Photo by Nate Meixell for Ombuds.

From Reflection to Imagination

Each participant received a short workbook that guided them through moments of solo reflection, small group conversation, and larger group dialogue. Prompts included:

Democracy is…

How do you see, feel, or touch democracy in the world around you?

What kind of space would facilitate democracy based on your definition?

What would it take to bring that imagined space to life?

The workbook was intentionally designed to balance introspection and collaboration — inviting people to consider their own lived experience of democracy before layering in the perspectives of others. In many ways, the process itself mirrored democratic practice: reflection, dialogue, negotiation, and synthesis.

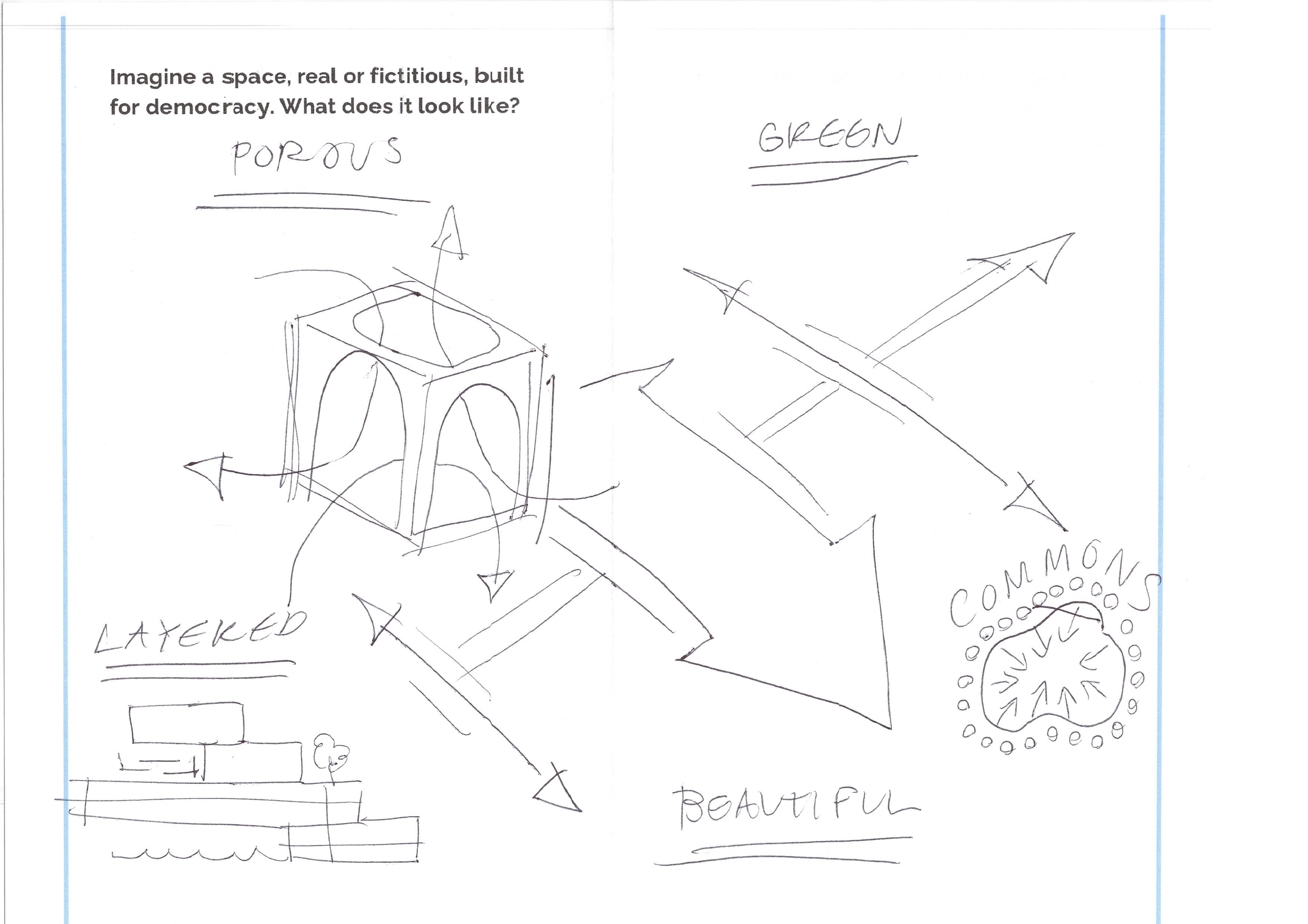

“Imagine a space built for democracy.” Participants’ sketches turned abstract values into spatial ideas.

Common Threads

Despite varied backgrounds and professional lenses, participants arrived at strikingly consistent ideas about what democratic spaces share.

Visibility, permeability, accessibility, and publicness came up again and again — qualities that make spaces open, legible, and welcoming to all.

The group also explored the power of analog encounters that happen by chance. We discussed how many of our most meaningful civic moments occur spontaneously: overhearing a debate at the park, stopping to sign a petition, or simply witnessing community life unfold in the street.

Participants emphasized that democratic design isn’t only about inviting participation, but also about allowing retreat. Spaces should support varying levels of engagement — giving people agency to participate actively, observe quietly, or reflect in solitude. In short: democracy requires room for both voice and pause.

Design Principles for Democratic Space

From those discussions, several principles emerged — not as prescriptions, but as guiding ideas for designers, planners, and civic leaders alike:

Visibility: Spaces seen from the public realm, where civic activity is visible and normalized.

Permeability: Easy to enter and exit; no physical or social barriers to participation.

Accessibility: Truly usable by all — regardless of age, race, or ability.

Discoverability: Capable of being “stumbled upon” naturally in daily life.

Publicness: No purchase, membership, or reservation required.

Varying levels of participation: Space for both gathering and solo reflection.

Interaction: Environments that spark conversation, connection, and social exchange.

Everyday Actions, Everyday Democracy

Before closing, we asked each participant to name one small action they could take to promote democracy in their daily life. I was surprised by how many participants arrived at the same conclusion:

They wanted to remove their headphones — to be more open to spontaneous interaction in public space.

That simple commitment carried enormous symbolic weight. It underscored how democracy begins with small gestures: noticing, greeting, and listening to others. Spaces can support this kind of openness, but so can the micro-decisions we make as individuals moving through them.

Design as Practice, Not Product

Perhaps most beautifully, the workshop itself became a model for democratic design — one that balanced self-reflection, dialogue, and collective synthesis. The structure mirrored the qualities participants described in their ideal spaces.

That realization has since informed our thinking about facilitation itself: what if civic engagement processes were designed like the spaces we want to create — visible, accessible, discoverable, and participatory?

Looking Ahead

Insights from this session will directly inform our forthcoming Facilitation Guide and Design & Policy Precedent Toolkit — practical resources that translate these ideas into actionable frameworks for communities, planners, and policymakers.

In the next post, we’ll explore Part III: Planning Neighborhoods for Collective Power — where participants reimagined land use planning with democracy at its core.

Until then, we invite you to reflect:

What everyday places — parks, sidewalks, cafés, stoops — make you feel most included in your community’s story?