Designing for Democracy: Planning Neighborhoods for Collective Power

What would a neighborhood designed for democracy look like?

That was the question at the heart of our third Designing for Democracy workshop — a hands-on exercise that invited participants to think like planners, designers, and neighbors all at once.

After two sessions exploring democratic values and spatial qualities, this event zoomed out to the neighborhood scale. The task: create a conceptual land use plan rooted in democracy. Participants were given a blank “plot of land” and asked to allocate spaces and uses — from parks to schools to civic centers — guided by their own definitions of what democracy needs to thrive.

Democracy in Plan Form

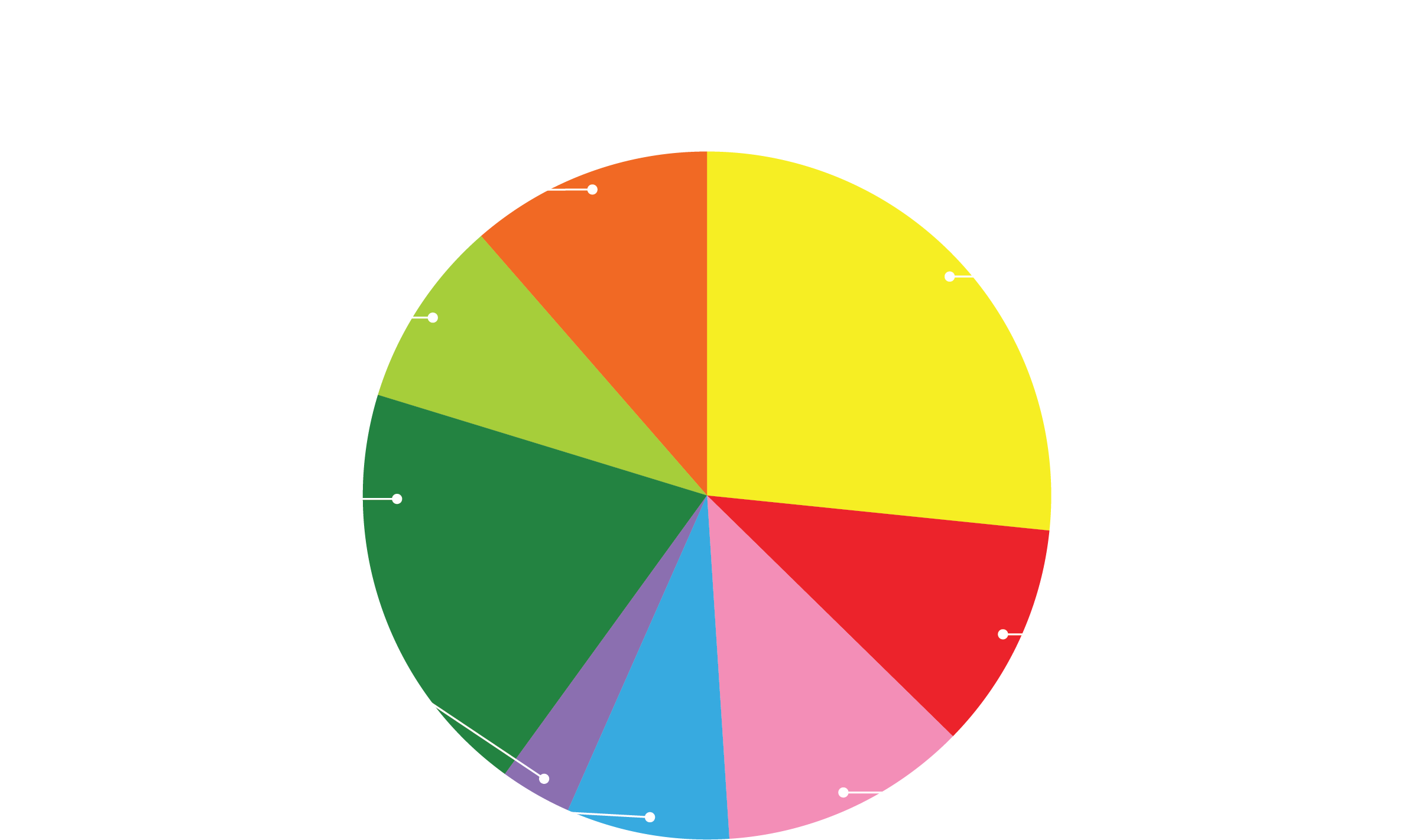

The activity wasn’t about technical accuracy or zoning regulations; it was about values translated into space. Groups arranged small squares representing land uses — greenspace, housing, commerce, civic institutions, and more — to form their imagined democratic neighborhoods.

It was fascinating to see what emerged. While layouts varied, several strong themes emerged:

Access to nature: Parks and greenspace were the first thing most groups plotted, building all other uses around shared natural environments for rest, gathering, and reconnecting with nature.

Food security: Many groups included urban farms and community gardens, tying nourishment to civic resilience.

Clean air and adaptive industry: Heavy industry had no place in their democratic neighborhoods, but light industry and reused industrial buildings were welcomed — signaling a balance between productivity and livability.

Convenience and accessibility: Equitable distribution of daily needs — schools, clinics, grocery stores — within walking distance of homes.

Access to decision-makers: Access to public representative offices directly within neighborhoods, so residents could more easily engage in governance and civic dialogue.

That last idea — embedding access to decision-making in the everyday fabric of neighborhoods — felt especially powerful. It reframed civic participation as something local and continuous, not episodic or distant.

Participants’ land use choices revealed a collective emphasis on greenspace, housing, daily amenities, and civic access — the building blocks of a democratic neighborhood.

From Quality of Life to Democratic Life

The exercise sparked lively discussion about how “designing for democracy” differs from more familiar frameworks like the 15-Minute City.

There’s obvious overlap: both value accessibility, convenience, and quality of life. But participants noted a key distinction — democracy adds the dimension of power. It’s not just about meeting needs efficiently; it’s about shaping the systems that meet those needs.

A neighborhood designed for democracy would make participation visible, make power accessible, and make dialogue possible. It would invite residents not only to live well, but to engage in decision-making processes — together.

But Also, What Is a Neighborhood?

One question from the start of the session still lingers: How do we define a neighborhood?

Is it defined by boundaries on a map, or by the social relationships that give a place meaning? What happens when our civic boundaries don’t align with our lived ones — when the community we feel part of doesn’t match the one that formally represents us?

These questions lie at the core of Designing for Democracy — reminding us that planning for democracy means designing systems that reflect how people actually connect, not just how geography divides them.

Looking Ahead

This workshop built the bridge between values and systems — helping participants see how everyday planning decisions reflect our collective priorities.

As we move toward our Facilitation Guide and Design & Policy Precedent Toolkit, these insights will inform how we translate democratic principles into both design and governance practice.

Next up: Part IV — Micro-Spaces and Everyday Participation, where we zoom back in to explore the small, often-overlooked sites where democracy is lived day-to-day — the bus stops, plazas, and parks that shape how we connect.

Until then, we invite you to reflect:

What elements of your neighborhood make you feel connected — not just to place, but to power?